Guest post from Shane Downing

Living and working in “Africa in Miniature” opened Shane Downing’s eyes to many things. As someone who is equally passionate about protecting the environment as he is eating, it was not until Shane’s 27 months as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Cameroon that he truly began to think about food security seriously. Now returned and (mostly) resettled into life back in San Francisco, Shane reflects on the similarities he sees between food security issues in his home country and his adopted country and recognizes that regardless of the cultural and geographical differences that exist between the two, an underlying togetherness proves that when it comes to food, we are not that different after all.

African Weight Gain

No one, especially my mother, expected me to gain weight when I left for Africa. But that’s exactly what I did. Besides the personal growth and resiliency and hardening that comes along with a Peace Corps service, I returned to the states a plumper version of the Shane that had arrived to Cameroon 27 months earlier. Two things you need to know. One, I am not a picky eater. Two, my indulgence of Cameroonian cuisine was never at the expense of the poor or starving. So push those images of me gallivanting across sub-Saharan Africa yanking meat kabobs out of children’s hands and shoveling bushels of yams into my mouth and listen to what I have to say about food security.

People often times will associate Africa with famine. They picture famished children, clinging to their mothers, skeletal, malnourished, on the brink of death. Those of you who are quick to stereotype, beware; whereas the world is a big place, so too is Africa and alas, so too is Cameroon. When it comes to size, the central African country is on par with California and is fittingly referred to as “Africa in miniature.” Why? Because the country spans from the Atlantic Ocean to Lake Chad, from Nigeria to the Congo River Basin and subsequently includes all volcanoes, beaches, highlands, mangroves, grasslands, rainforests, mountains, deserts, and rivers within that area.

This diversity makes Cameroon a vibrant place, both from a cultural and a culinary standpoint. Cameroon produces enough food to be one of the continent’s few food exporters. Agriculture forms the backbone of the country’s economy and is rooted in large swaths of fertile soil and favorable growing conditions. But even I need to be conscious of perpetuating stereotypes, which will be tough considering Cameroonians come in all shapes and sizes, skinny to obese, malnourished to diabetic.

There are parts of Cameroon where food is difficult to come by, regions that are experiencing severe droughts and desertification and regions that are so entangled by the rainforest that the only protein available is in the form of threatened species of wild animals such as apes and monkeys. There are also regions where any seed that touches the soil grows and people might be two or three times wider than their leaner compatriots.

So, can we define Cameroon as a food secure country?

Well, not exactly. Even though the country attempts to spread out its agricultural bounty between the haves and the have-nots, Cameroon struggles to capture all three aspects of food security: availability of food, access to food, and utilization of food. Availability and access are, for the most part, accomplished as a result of subsistence farming, intra-national movement of homegrown crops, and favorable growing conditions. As a country, Cameroon struggles with how food is used – people either boil out all of the nutrients from their vegetables or drown their dishes in liters and liters of palm oil.

Just as we must resist the urge to drape blanket statements over the entirety of Africa, so too must I avoid casting an overarching, deceiving conclusion about food security for the entirety of Cameroon. It’s too large, complex, seasonal, skewed, misleading, blah, blah, blah.

The key to food security is honing in to what’s going on at the household level. What socioeconomic barriers, cultural norms, and environmental realities exist that affects the availability of food that a family is able to access and use on a day-to-day basis?

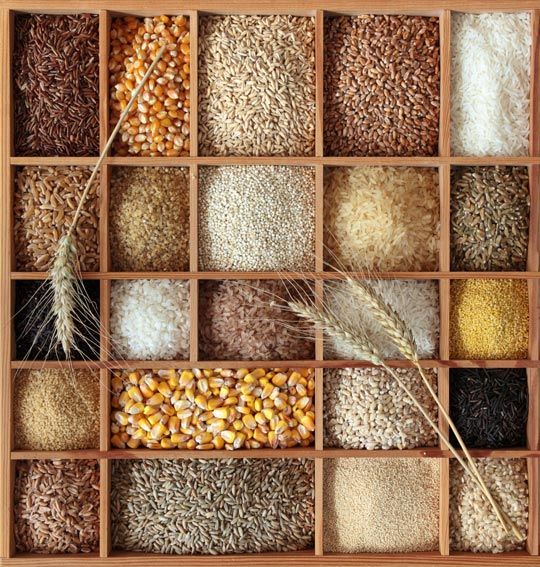

Does a family have food available to them? It’s not just yes or no. Do they have primarily starchy and/or carbohydrate heavy crops available to them or do they have a diversified diet (think the food pyramid). There’s a nutritional difference between a plate of plain white rice and a plate of the same rice, two small pieces of meat, and a serving of vegetables.

Who has access to the food that’s available in the home? Are the men served first and subsequently given the majority or all of the protein (meat and fish) in the dish? When do the women eat? Who is making sure the three year old is getting the same access to the communal plate as her ten-year-old brother? Is a pregnant or nursing woman getting access to a range of vitamin and mineral rich foods that are essential to the health of her and her baby?

And how is the food being used? Meat and vegetables are good things, yes, but when they are smothered in palm oil, that meal loses some of its nutritional value. Are all the vegetables eaten in one sitting, leaving the starches unaccompanied for the majority of meals?

Think about these same questions through the lens of what life is like in the United States? Is America a food secure country? I’m not convinced. Do all families have access to locally grown, organic, pesticide and hormone free meat and produce? No. Do all families have access to fast food chains and cheap convenience stores? Yes. Children are at the mercy of what their parent(s) feed them and mothers and fathers are at the mercy of what they can and cannot afford at the grocery store. And alas, food security is something that should be addressed at the family level, whether that’s a single father with two kids in the suburbs, a nuclear family in the city, or a 32-year old single female living life as a young professional and living alone.

Not all food is created equal. Although it is seemingly bountiful, people’s access to quality, safe, and healthy food is limited by economics and culture regardless of geographic location. I am not going to step up onto the paleo soapbox or Evangelize you with talk of a vegetarian lifestyle, but I will say that food security – availability, access, and use – is just as much of an issue in the United States as it is in Cameroon.

Cameroonians say “nous sommes ensembles,” or “we are together” a lot. When I returned home to the states after two years in Peace Corps, this togetherness was a very real sentiment I felt. The overflowing produce aisles and processed snacks packed into grocery stores initially overwhelmed me when I walked into life back in America. But in Cameroon, I also remember finding myself overwhelmed, walking through markets those first few months, albeit, for a whole host of reasons.

When it comes to food, Cameroon, the United States and, in all actuality, the rest of the world, we are together in pursuit of a more food secure today and a more food secure tomorrow. There is a lot of room to grow. Even though conditions vary and are sometimes harsh and limiting, with the right blend of education, policy, and science, food security can begin to take root in the public’s mind, both home and abroad, and can sprout fruitful solutions for the benefit of family nutrition around the world.

This is what we as Peace Corps Volunteers attempt to promote in our towns and villages across Cameroon. It is our challenge and our duty, for those of us volunteers who have returned, to continue to carry this banner of food security as we reintegrate into American life, shaped and impacted by our transformative experiences abroad, ready to maintain our role as mediators of these cross-cultural, gastronomic exchanges.